Guest Editorial: Injustice in Massachusetts — Two Years in Jail for One Joint 4/14/06 by Anthony Papa of 15yearstolife.com

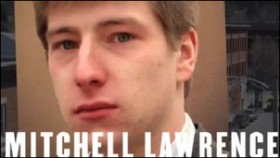

The drug war reached the pinnacle of cruelty when Mitchell Lawrence, an 18-year-old Berkshire County teen, was sentenced to two years in jail for the sale of one joint worth of marijuana — about a teaspoon.

The drug war reached the pinnacle of cruelty when Mitchell Lawrence, an 18-year-old Berkshire County teen, was sentenced to two years in jail for the sale of one joint worth of marijuana — about a teaspoon.

Lawrence was found guilty of distribution of marijuana, committing a drug violation within a drug-free school zone, and possession after he sold a 1.12 gram bag of marijuana to an undercover police officer for $20.

While this outrageous case happened in a sleepy burg in Massachusetts, the case of Mitchell Lawrence is one of countless tales of drug war madness that takes place on America’s streets daily.

On June 30, 2004, Detective Felix Aquirre, employed by the Drug Task Force, was assigned the duty of buying drugs from kids who hung out in a parking lot in Berkshire County in Massachusetts. Merchants had complained to police about the groups of kids that hung out there. Lawrence was there with his pipe and a few marijuana buds of pot in a plastic bag. He had no idea the parking lot was less than 1,000 feet from a preschool located in the basement of a church, nor did he know this parking lot was the site of a police sting operation.

The undercover cop approached Mitchell and asked him if he had some weed. Lawrence pulled out a small bag of marijuana. The cop offered him a twenty dollar bill. Lawrence hesitated. The cop insisted. Lawrence, who had seen the cop hanging out with other kids, motioned the cop to follow him up the street where he intended to smoke with him. The cop waved the $20 in his face. Like a carrot dangling on a string, Mitchell, who was broke at the time, took the money. It was the only time Lawrence ever accepted money in exchange for marijuana.

In the months that followed, the cop approached Lawrence again for marijuana. This time, however, Lawrence refused. Weeks later, a crew of undercover cops stormed Lawrence’s home and placed him under arrest. On March 22, 2006, Lawrence was sentenced to two years in prison.

This story was eerily familiar to me. In 1985, I was the subject of a police sting operation where I passed an envelope containing four ounces of cocaine to undercover offers in Mount Vernon, New York. I was set up by someone who offered me $500 to transport the package. The individual who introduced me to the cop was an informant facing life in prison. He was offered a deal — the more people he got involved, the less time he would serve. He took the deal, set me up and I received a sentence of 15 years to life under New York’s draconian Rockefeller Drug Laws.

The disproportionate sentence of Lawrence was handed down one day before the release of a national report by the Justice Policy Institute (JPI): “Disparity by Design: How Drug-free Zone Laws Impact Racial Disparity and Fail to Protect Youth,” which includes research from Massachusetts.

The JPI study, commissioned by the Drug Policy Alliance, found that drug-free zone laws do not serve their intended purpose of protecting youth from drug activity. The Massachusetts data on drug enforcement in three cities found that less than one percent of the drug-free zone cases actually involved sales to youth. Additionally, Massachusetts researchers found that non-whites were more likely to be charged with an offense that carries drug-free zone enhancement than whites engaged in similar conduct. Blacks and Hispanics account for just 20 percent of Massachusetts residents, but 80 percent of drug-free zone cases.

“School zone laws have remained unchanged in Massachusetts because the legislature has been promised that prosecutors use discretion,” said Whitney A. Taylor, executive director of the Drug Policy Forum of Massachusetts. “Unfortunately, the life of a young man has been sacrificed, proving that discretion is not being used and that the law must be changed.”

Lawrence was not the only arrest made in an undercover drug operation in the summer of 2004. There were a total of 18 others, including five young people who are still awaiting trial for alleged sales that took place at the same Great Barrington parking lot.

District Attorney David F. Capeless is the man behind Berkshire County enforcement and entrapment. Capeless is a hard-nosed drug war zealot, who insists that these laws are effective in combating drug use — even if it means ruining a young man’s life in the process.

Lawrence was set to graduate from high school this spring. Instead, he will watch his fellow classmates graduate from his prison cell.

The common thread between my case, Mitchell Lawrence’s case and drug free school zones nationally is the abuse of power from the prosecutors through the application of mandatory minimums. These laws handcuff judges and force them to impose harsh sentences.

Lawrence’s conviction inspired a group of concerned Berkshire County residents to seek Capeless’ ouster in the upcoming district attorney race. Defense attorney, Judith Knight answered the call to fill this role. Knight, a former assistant district attorney for Middlesex County said, “Lawrence’s conviction was the tipping point” for her decision to run against Capeless in the upcoming Democratic primary election in September.

Knight says that “a tough prosecutor is tough on crime and also has the ability to demonstrate compassion and insight when the case calls for it.”

Knight, with her “Judy for Justice” campaign hopes to follow in the footsteps of David Soares, who ran for district attorney and defeated Paul Clyne in Albany, New York in 2004. Soares ran a race primarily on the platform of Rockefeller Drug Law reform. He easily defeated the sitting district attorney who refused to change his views on the draconian drug law legislation of New York.

It is heartening that communities like Berkshire County are fighting back and attempting to hand reckless district attorneys and other politicians the pink slip if they chose to destroy lives and indiscriminately apply laws in a way does more harm than good, ultimately, without keeping our streets any safer.

Article republished from StoptheDrugWar.org under Creative Commons Licensing

Below is a 2006 video from the Drug Policy Alliance on Mitchell’s plight: